Read Along Worksheet Week 4 (Free!)

We’re getting close to part in The War of Art where we transition from defining the enemy to defeating the enemy—although I haven’t been able to keep myself from exploring the ways we face off with Resistance at least a little in our lives. It’s a lot harder to sit with the uncomfortable knowledge that Resistance exists within us, that we have self-sabotaging tendencies, than it is to jump into solutions. But all of this has been important: Knowing the shape of self-sabotage, its signs and symptoms, empowers us to recognize it. If comic book invisible villains have taught us anything, it’s how hard it is to fight something you can’t actually see.

Facing Our Fears

Our first passage from The War of Art describes the significance of fear: “…the more fear we feel about a specific enterprise, the more certain we can be that that enterprise is important to us and to the growth of our soul” (40). Fear is about safety. Familiar is safe. Stable is safe. The things that are familiar and stable won’t evoke fear in us.

When I was a beginning seamstress in my early twenties, the patterns I purchased became familiar and safe. Follow the lines. Stitch the pieces together step by step. I kept to the simple things. Cloaks? Yes! Cloaks are very simple. Big billowing fabric that can hide minor mistakes in their folds. I love cloaks.

A friend came to me with a good-quality wool coat she’d acquired and asked me if I could tailor it to fit her. There was no pattern, no clear crisp lines to follow. There would be no room for billowing fabric to cover up mistakes. Even though I knew conceptually what she was asking of me was most likely in my wheelhouse, I was afraid. I told her I didn’t want to ruin it, and she replied that if even if I ruined the coat, it was fine. The coat was useless to her in its current state. If I made a mistake and ruined it, it would be just as useless.

She saw something I couldn’t see about myself because the fear held me: I would not ruin the coat.

When I took that next step forward and altered her coat, it wasn’t by any means an amazing perfect masterpiece of sewing prowess, but it absolutely did the job. Both for her, so she’d have a warm winter coat, and for me. I discovered I didn’t need to follow the pattern down to every line and letter. If I worked on understanding how each panel of fabric fit the wearer, I’d be able to alter a pattern or even create my own. The fear I had (and the confidence my friend had in me) pointed me toward growth in pursuing a casual, enjoyable hobby.

There are other kinds of fear that serve as markers for other things, but fear of own creative endeavors mark their significance in our lives. When you are looking at your creative project and you feel afraid, lean into it. Explore where that fear is coming from, why this creative project does matter, and remember: Whether you don’t do the thing, or you do it terribly, you’re in the same place. Taking a chance on your creative project is the only way toward something wonderful.

Doing the Work

Pressfield recounts the moment in his life when he ended up in New York driving a cab, at rock bottom, when he pulled out his typewriter and did the work. After he did some writing, he found the energy to do ten days’ worth of dishes. He says, “I hadn’t written anything good. It might be years before I would, if I ever did at all. That didn’t matter. What counted was that I had, after years of running from it, actually sat down and done my work” (50).

Doing our work doesn’t magically fix our lives or heal us of all ails. What it can do, though, is remind us of who we are. Today, when I’m writing this, right now, I had a rough day at work. I talked it out with my husband and my best friend. I looked at the clock, saw I had enough time to at least make a start of an outline for this post, and settled in intending to give it ten, fifteen minutes, then go crochet. An hour and a half later, I barely felt the time pass. Doing this work doesn’t change the fact that I had a rough day and it doesn’t fix all the problems around me. But it certainly hasn’t made those problems worse, either.

I can’t wait for a perfect day with no problems to make creative progress because that day will never exist—not even during summer break. I can’t wait for my latest retina lesion to heal up after the treatment I received last week. I also can’t pretend my problems don’t matter. They do. I’ve got to factor those into my life. There are plenty of days I can’t get the work done (and I’m not going to guilt or shame myself or anyone else for taking the breaks they need). I’ve just got to take those ten minutes where they come, and enjoy it when ten minutes becomes an hour and a half.

Finding Flow

Pressfield describes that experience: “It is a commonplace among artists and children at play that they’re not aware of time or solitude while they’re chasing their vision. The hours fly. The sculptress and the tree-climbing tyke both look up blinking when mom calls, ‘Suppertime!'” (44-45)

That’s flow, the peak human experience, and everyone can enjoy it. Csikzentmihalyi explains, “In our studies, we found that every flow activity, whether it involved competition, chance, or any other dimension of experience, and this in common: It provided a sense of discovery, a creative feeling of transporting the person into a new reality” (74). Pressfield’s artist, child, sculptress, and tree-climber are all experiencing flow. But how do we get there? How do we hold onto it for any length of time?

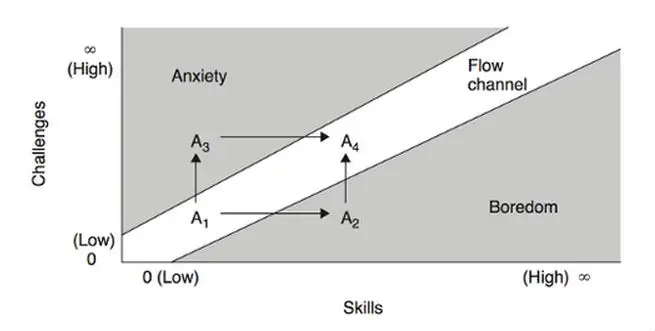

Pressfield says, “In order for a book (or any project or enterprise) to hold our attention for the length of time it takes to unfold itself, it has to plug into some internal perplexity or passion that is of paramount importance to us” (46). Csikzentmihalyi has a diagram that helps illustrate that point perfectly:

If you aren’t someone who gleans information easily from graphs, here’s what it means: To achieve flow, find the perfect intersection between challenge level and skill level. A1 represents an activity that is low skill, low challenge, but where the skill level and challenge level meet, it’s a chance to experience flow. The first time a child climbs a tree, just getting up onto one branch is all the skill they’ve got, so the challenge level of getting up to that lowest branch matches their skill level, and they’ll enjoy it. As their tree-climbing skills improve, though, that first branch is too easy, and they slide over into the A2 position of boredom. It’s too easy to climb the lowest branch. Done that a million times. Skill: Acquired. Time to reach for the next branch higher, or find a different tree, or seek a different activity entirely that raises the challenge level.

A3 on the diagram is why giving my high school students challenging texts with no support or skill development won’t help them grow: If the challenge is too high and you don’t have the skills to meet it, you’re going to experience anxiety. First, I have to build up the students’ skills and background knowledge. Then they can tackle the challenging text and find flow instead of anxiety. (Ideally.)

“It is this dynamic feature that explains why flow activities lead to growth and discovery. One cannot enjoy doing the same thing at the same level for so long. We grow either bored or frustrated; and then the desire to enjoy ourselves again pushes us to stretch our skills, or to discover new opportunities for using them” (Csikszentmihalyi 75).

Accessing Our Own Flow

Different people value different skills. Different people view challenges in different ways. I absolutely love listening to all kinds of tutorials and process videos online, not because I expect to become an artist, but because when a person who has experienced flow in the act of creation describes that experience, it resonates with something deep within me. They describe and frame the challenges they faced. They demonstrate the skills they possess and how they use those skills. They don’t only breathe something into the universe–they share the breathing with anyone who cares to listen. I love it.

It also means I understand that flow is personal. One person’s flow activity is someone else’s absolute snore fest. We can’t rely on a single pre-scripted path forward to find flow. So, it’s not about the one right way to be creative. It’s about learning to recognize the invisible forces at work in our own minds and thought processes–the shape of the Resistance inside ourselves, the truest passion that burns in our hearts, the skills we possess to defend our fiery hearts, and the challenges that best fuel the flame.

Stephanie Gildart weaves tales in writing and crochet. As a child growing up near Seattle, she checked out so many books that she memorized her library card number. She received her MA/MFA from the Simmons University Center for the Study of Children’s Literature in Boston. When she isn’t writing or teaching English, she loves to crochet amigurumi dolls of fantasy creatures, play tabletop roleplaying games and board games, and sing.

Read Paxwood

Read Paxwood