As I reread the first sixteen pages of The War of Art, I was pulled in by Pressfield’s experiential descriptions of the Resistance. From the first page, where he recounts what a day of writing is like for him, through declaration that we feed Resistance with our fear on page sixteen, the tangible imagery grabs hold.

I know, of course, that we’re talking about mental processes here. Any writer or creative knows at least to some extent that creative blocks happen, and these things are inside our head. But things that happen inside our heads shape our consciousness, our focus, and our experiences.

In Flow, Mihaly Csizentmihalyi defines consciousness as “the result of biological processes. It exists only because of the incredibly complex architecture of our nervous system, which in turn is built up according to instructions contained in the protein molecules of our chromosomes.”

Some people are able to better understand their own innate nature and potential through those molecules, our bodily processes, hormones, and brain chemistry. As someone with an autoimmune disorder, I have deep respect for those people because I absolutely need medication to compensate, and it has made a world of difference.

Both Csizentmihalyi and Pressfield focus on a form of analysis that speaks to my nature as a storyteller. Their writings deal “directly with events–phenomena–as we experience and interpret them, rather than focusing on anatomical structures, neurochemical processes, or unconscious purposes that make these events possible” (Csizentmihalyi 25-26).

Pressfield’s writing leans to the dramatic, and Csizentmihalyi to the scientific, but both both speak to me, which is why I’ll be putting them in conversation with each other.

When Pressfield describes innate genius in the forward as “an inner spirit, holy and inviolable, which watches over us, guiding us to our calling,” it speaks to me. Pair that with Csizentmihalyi’s description of attention: “Attention is like energy in that without it no work can be done, and in doing work it is dissipated. We create ourselves by how we invest this energy. Memories, thoughts, and feelings are all shaped by how we use it.” So, genius is more than a whisper of potential. Genius, consciousness, our inner self, grows from how we use our attention.

And consciousness only has so much space. We can’t be constantly aware of everything. We’re human, so we have to spend the energy of attention carefully and wisely.

When Pressfield declares “I looked everywhere for the enemy and failed to see it right in front of my face” I thought I knew exactly what he meant. I’ve spent enough time blaming myself for my problems and creative blocks, kicking myself when I’m down, and it’s so incredibly easy for me to say that I’m the problem.

But the thing I’ve found, both by reading through this book and in my own experience: Self-blame is just another mask of the Resistance, and Resistance “cannot be reasoned with. It understands nothing but power” (10). As much as Resistance is inside of me, inside of all of us, it is not us, and it’s not our fault.

At least, not exactly.

Our lovely human consciousness is constantly bombarded with “information that conflicts with existing intentions, or distracts us from carrying them out” (Csikszentmihalyi 36).

I intend to sit down to get some writing done, but my dog keeps pawing at my leg. Now I have to figure out what my sweet little fussy Fox wants.

Or, I go down to the basement to grab a reference book and discover that the basement has partially flooded.

Or, I’m hounding myself with negative self-talk because I’m not living up to my greatest potential.

Small daily experiences like these, large crises and life-altering revelations, or every experience with a magnitude between those two extremes contribute to disorder in our thoughts. We lose focus. Our attention gets pulled in too many directions, we spend all our energy, and these things can become “psychic entropy, a disorganization of the self that impairs its effectiveness” (Csikszentmihalyi 37).

Resistance is psychic entropy. It’s a deterioration of focus, spending our attentive energy on too many different things, never quite managing to come back to our own self, our genius. And, this psychic entropy is like the laundry, dishes, and all the other chores in our lives. It’s pretty much inevitable. Every day, we gain new experiences. Every day we have to figure out what to do with them. Csizentmihalyi writes: “Every piece of information we process gets evaluated for its bearing on the self. Does it threaten our goals, does it support them, or is it neutral? … A new piece of information will either create disorder in consciousness, by getting us all worked up to face the threat, or it will reinforce our goals, thereby freeing up psychic energy” (39).

Every single experience gets filtered through our minds, and we experience so much day after day. Pressfield writes, “The warrior and the artist live by the same code of necessity, which dictates that the battle must be fought anew every day” (14). It’s an ongoing process. We’ll never reach some plateau where creativity filters purely down from heaven. Rather, like every other human being, we’ll have good days, average days, bad days. We’ll do our best to set ourselves up for success where we can, and roll with shifting tides of this war.

If terminology like “Resistance” and “the enemy within” (10) get you to pay attention to these forces within you and build your confidence to face them, hold on to it. Let it free up some psychic energy as it becomes shorthand for the new information you’re developing as you solidify your understanding of the shape of things inside of you.

But if it’s perpetuating negative self-talk, call it entropy or mental laundry and remember that it does not define you.

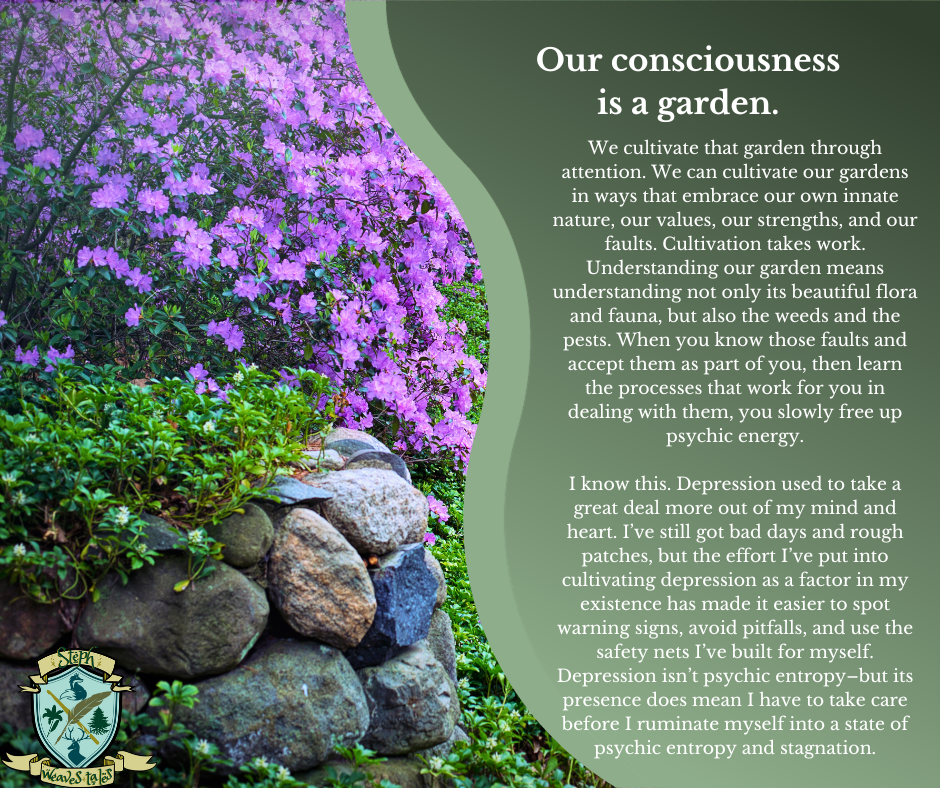

Another image that might help:

Our consciousness is a garden. We cultivate that garden through attention. We can cultivate our gardens in ways that embrace our own innate nature, our values, our strengths, and our faults. Cultivation takes work. Understanding our garden means understanding not only its beautiful flora and fauna, but also the weeds and the pests. When you know those faults and accept them as part of you, then learn the processes that work for you in dealing with them, you slowly free up psychic energy.

I know this. Depression used to take a great deal more out of my mind and heart. I’ve still got bad days and rough patches, but the effort I’ve put into cultivating depression as a factor in my existence has made it easier to spot warning signs, avoid pitfalls, and use the safety nets I’ve built for myself. Depression isn’t psychic entropy–but its presence does mean I have to take care before I ruminate myself into a state of psychic entropy and stagnation.

That happens. Sometimes, our mental gardens grow wild with weeds and pests. Often it’s because there is too much going on in the world around us to take any time to care for ourselves, or because something has happened that totally shattered our self-image. When a relationship you’ve cultivated for years comes to an end unexpectedly, when that creative project is constantly met with apathy from everyone around you, when your enthusiasm is answered with disdain, it wears you down. One thorny weed you just don’t have the energy to pull becomes twenty. A sprig of something green you thought would be lovely in your garden turns out to be kudzu that blankets your garden and denies all other plantlife access to sunlight.

It’s easy to say it’s a choice to tend to our consciousness–because, technically, it is. We’ve also got to make choices about financial stability, physical safety, and how we act in the world around us. And we’ve got to deal with the consequences of other people’s choices. Those impact us, too.

Whether you’re the one that’s in the depths of psychic entropy or someone else is, remember: “Everyone who has a body experiences Resistance” (13).

So, we’re all in this thing together. We don’t know everyone’s exact experiences, but we can also choose to meet others and ourselves with empathy rather than judgment.

You don’t restore a garden by complaining about the weeds. You can’t win a war with friendly fire.

When you have that chance to breathe, you start from where you’re at. Assess the situation. Accept it for what it is. Then, do one tiny thing to make it better.

In our next week’s reading, we’ll look at the allies and symptoms of Resistance, reading pages 17 through 28. As a head’s up, pages 26 through 28 contain potentially triggering views on medication, medical diagnoses, and victimhood. For me, it’s an opportunity to roll my eyes real hard, but please feel free to skip those pages. You know yourself best.

Works Cited:

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2008.

Pressfield, Steven. The War of Art. Black Irish Entertainment, 2002.

Stephanie Gildart weaves tales in writing and crochet. As a child growing up near Seattle, she checked out so many books that she memorized her library card number. She received her MA/MFA from the Simmons University Center for the Study of Children’s Literature in Boston. When she isn’t writing or teaching English, she loves to crochet amigurumi dolls of fantasy creatures, play tabletop roleplaying games and board games, and sing.

Read Paxwood

Read Paxwood