Read Along Worksheet Week 2 (Free!)

Although Steven Pressfield describes Resistance as its own entity, something that we could imagine as existing outside of ourselves, in this week’s reading we get the clear, simple, straightforward statement: “Resistance by definition is self-sabotage” (Pressfield 19).

When Pressfield describes Odysseus’s crew releasing those adverse winds right at the end of the journey, operating on the assumption that the bag contained gold that Odysseus was trying to keep from them, it’s easy to feel like Odysseus and not like the crew.

We’re both Odysseus and the crew in the situation, though. We are the one who wants to make the journey smoothly, and we are the ones who second-guess our own decisions. We’re the one who recognizes and avoids adversity that could get in the way of our best laid plans, and we’re the ones who decide to open up the bag of adversity hoping to find gold inside. We fulfill all these roles in our journeys without any outside help.

The underlying causes of self-sabotage in all its forms are a lot harder to identify than the symptoms, but symptoms help us to recognize when something is off-balance inside of ourselves. I’m going to run through the symptoms in a different order than in The War of Art, and I’ll call them slightly different things, too.

Procrastination

Procrastination is only self-explanatory in that we know procrastination means we’re putting something off. Like any of these symptoms, the underlying cause of procrastination can vary widely. It’s often treated like some kind of moral failure. You just have to choose to work, and then the work gets done.

I agree with Pressfield’s sentiment when he writes: “There never was a moment, and never will be, when we are without the power to alter our destiny. This second, we can turn the tables on Resistance” (22).

I just have to acknowledge that turning the tables on procrastination requires understanding where the procrastination comes from.

Sometimes procrastination stems from perfectionism, that need to make sure that everything is exactly the way it needs to be. The exact right workspace, the exact right time of day, the exact right words in the exact right order. Perfectionism can grow as a fear response–that if it’s perfect, no one can criticize or attack you. The standards of perfection might be something you’ve set for yourself or someone else’s rigid expectations.

Sometimes it’s an executive functioning thing. Some people have trouble with prioritizing, knowing how to get started, breaking tasks down, dealing with interruptions, adjusting their plans to address circumstances outside of their control.

Procrastination can look the same from the outside regardless of the causes. We see ourselves sitting still and not moving when we have the time and resources and we could be making progress. Yelling, “Work harder!” isn’t going to fix the problem of procrastination.

If my brain makes a noise like a fork in a garbage disposal–thanks for that image, Chidi!–every time I try to get started, I can procrastinate. I can avoid whatever action put my brain in motion just so I don’t hear the fork-in-a-garbage disposal noise. I can fear the garbage disposal is under control of a paranormal force that will destroy my hand if I try to remove the fork. But I can also choose, in that moment, to try to figure out what the fork is and how to remove it safely. Finding the underlying cause of procrastination is worthy work–unless that becomes the new excuse, one symptom evolved into another.

Namely…

Pleasure-Seeking and Consumerism

In The War of Art, Pressfield names sex and self-medication as symptoms of resistance. The word “sex” catches people’s attention but is one narrow aspect of pleasure-seeking behaviors. His self-medication passage leans toward invalidation of actual medical conditions, so I’m renaming and reframing both of these issues.

I’ve got depression, an autoimmune disorder, and an eye condition that are all definitely not just in my head (although my eyes are literally in my head, but you know what I mean). I love my neurospicy friends who are absolutely willing to call out the ways that society imposes certain expectations on our behaviors. Finding the label that helps me understand who I am and how I fit (or don’t fit) has made so much difference in my quality of life.

The idea here is self-sabotage can involve trying to find quick fixes or excuses for complex problems. Even the most expensive diamond-encrusted fix that a marketing company can throw in your path isn’t worth a penny if it doesn’t actually help.

When something that should give you pleasure leaves you feeling empty, “the more empty you feel, the more certain you can be that your true motivation was not love or even lust but Resistance” (23).

In Flow, Csikszentmihalyi points out the way that television can be used as a filler when someone is experiencing too much solitude: “While interacting with television, the mind is protected from personal worries. The information passing across the screen keeps unpleasant concerns out of the mind. Of course, avoiding depression this way is rather spendthrift, because one expends a great deal of attention without having much to show for it afterward” (169).

It’s incredibly easy to dig on television watching, gaming, and other purely pleasurable activities as wasted time that could be used for creative projects. That doesn’t mean you have to exchange pleasure for grinding all day every day. Flow is literally all about how important enjoyment is to our lived experiences, and how to find that enjoyment in the work we care most about. There’s nothing wrong with enjoying life.

It’s the emptiness we’ve got to watch out for. When I can’t find lasting joy in a restful or pleasurable activity, I know it’s time to take stock–especially as someone who lives with depression.

Another part of the self-sabotage can be that pleasurable experience that comes from buying a product or service. Whether it’s the medical industry, parenthood, education, publishing, or pretty much any field you could possibly want to explore, there are some people who genuinely have resources to help and deserve compensation for the help they provide. There are predatory professionals whose goal is to make money regardless of whether or not they actually help anyone at all. And, there are so many consumers who are willing to throw money at a problem and hope their purchase will fix it, then–whether it would help or not–the purchased solution sits forever in a closet.

If you’re constantly looking for something you can buy to make your creative process better, and you’ve got a new toy every month and no new completed creative works to show for it, you might just be dealing with some Resistance.

With both pleasure-seeking and consumerism, if it’s not helping you make progress, it’s self-sabotage. It can be another way to procrastinate, which means that you need to look for what you’re avoiding and why you’re avoiding it. You can also be bamboozled by the marketing industry into thinking these things are going to help you succeed.

Instead of throwing money at the problem, sometimes you need to look for the solutions that actually fit your personal resources and lifestyle. Take time to ask yourself: Why do I think this is going to help me? What am I actually looking for? What supports or resources do I already have access to that would help me accomplish my goals? And, what’s the return policy on this particular purchase?

Trouble, Self-Dramatization and Self-Martyrdom

Another symptom of self-sabotage is the trouble we make for ourselves and justifications we create about things that may be outside of our control. I’m grouping these three symptoms together even though each is separated out in The War of Art. (Self-Martyrdom is referred to as Victimhood, but it’s a term that is so close to victim-blaming, so I will be using self-martyrdom instead.) They all relate to the way that we rope other people into our self-sabotage.

Bad things happen to us and around us, things we may not have control over. Being human, living in the world, that just means we’re going to have problems to deal with. All three of these symptoms of Resistance are less about the external problems that actually exist in the world and more about our own coping mechanisms.

Csikszentmihalyi describes a scenario where a fictitious person who loses their job can choose to “withdraw into himself, sleep late, deny what has happened, and avoid thinking about it” (199). That’s procrastination. Or, “He can also discharge his frustration by turning against his family and friends”–making trouble and creating new drama in an attempt to get away from the pain of job loss.

It’s easy to imagine a person in that situation casting themselves as the martyr who was fired by a cruel boss, seeking sympathy in their hardship. Sympathy, attention, comfort, these things provide a temporary sense of relief. Creating drama or looking for trouble can give a quick mood boost or a distraction from the things we can’t control.

These are all ways of coping with stress. Csikszentmihalyi talks about three factors that help us handle stress: First, external support from family, friends, and community; second, “psychological resources such as intelligences, education, and relevant personality factors” (199); and third, coping strategies.

Two broad categories of coping strategies are regressive coping and transformational coping. Regressive coping is anything that makes you turn inward. Transformational coping is when a person takes the situation and redefines it or redefines themselves, using the moment to rise from the ashes like a phoenix into something new. Csikszentmihalyi acknowledges that “few people rely on one or the other strategy exclusively” (199). Sometimes we regress; sometimes we transform. Sometimes we need a cocoon so that we can take the time to rest and become that butterfly.

The thing Csikszentmihalyi notes that really stuck with me is this: “Sooner or later everyone will have to confront events that contradict his goals: disappointments, severe illness, financial reversal, and eventually the inevitability of one’s death. Each event… threatens the self and impairs its functioning… Without [transformational coping] we would be constantly suffering through the random bombardment of stray psychological meteorites” (202).

I don’t have a random bombardment of actual meteorites pelting my life, but I do have an eye condition similar to macular degeneration. My retina has many miniscule spots of inflammation that could, at any time, become lesions that create permanent distortion and scarring in my vision. Can’t correct that with glasses. In the fifteen years I’ve been dealing with my eye condition, I’ve had to regularly confront the fact that some day I could lose visual acuity to a point that I can’t drive safely, can’t read text or music on a page, can’t see what I’m writing as the words unfold into sentences and paragraphs.

So, I’ve made a point to learn to crochet in dark rooms, by touch, both so that I can crochet at a movie theater and I can have a craft that comforts me no matter what happens to my eyes. I’ve familiarized myself with digital resources that convert speech to text and text to speech. Instead of avoiding thinking about it until another lesion forms, I’ve taken time to address it. Whatever happens, whether scientific developments keep on improving to a point where I can get a retina transplant if things get real bad, or a preventative treatment is developed to reduce the retinal inflammation, or I do lose my sight, by acknowledging and processing my experiences and fears, I’ve opened myself up to many futures where I’ll continue to have an enjoyable life.

Doing the Work

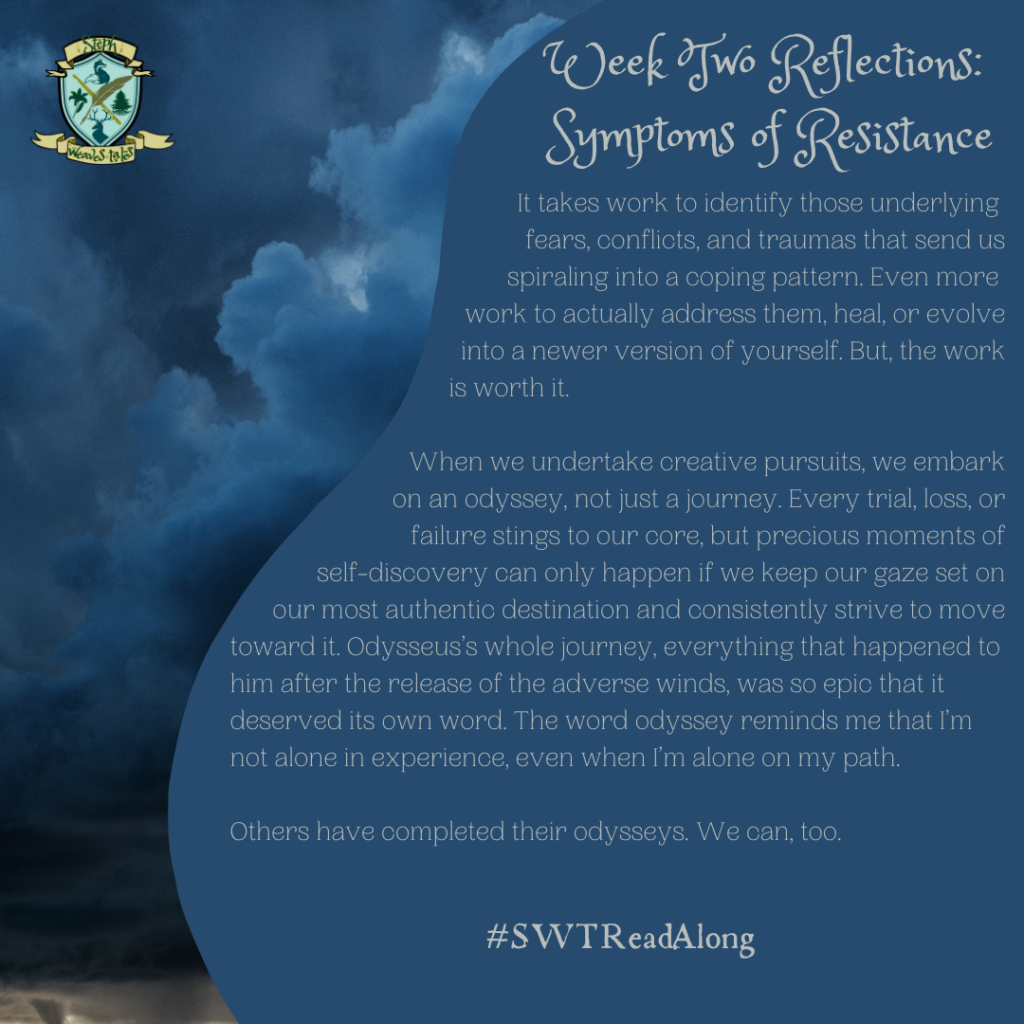

It takes work to identify those underlying fears, conflicts, and traumas that send us spiraling into a coping pattern. Even more work to actually address them, heal, or evolve into a newer version of yourself. But, the work is worth it.

When we undertake creative pursuits, we embark on an odyssey, not just a journey. Every trial, loss, or failure stings to our core, but precious moments of self-discovery can only happen if we keep our gaze set on our most authentic destination and consistently strive to move toward it. Odysseus’s whole journey, everything that happened to him after the release of the adverse winds, was so epic that it deserved its own word. The word odyssey reminds me that I’m not alone in experience, even when I’m alone on my path.

Others have completed their odysseys. We can, too.

Stephanie Gildart weaves tales in writing and crochet. As a child growing up near Seattle, she checked out so many books that she memorized her library card number. She received her MA/MFA from the Simmons University Center for the Study of Children’s Literature in Boston. When she isn’t writing or teaching English, she loves to crochet amigurumi dolls of fantasy creatures, play tabletop roleplaying games and board games, and sing.

Read Paxwood

Read Paxwood